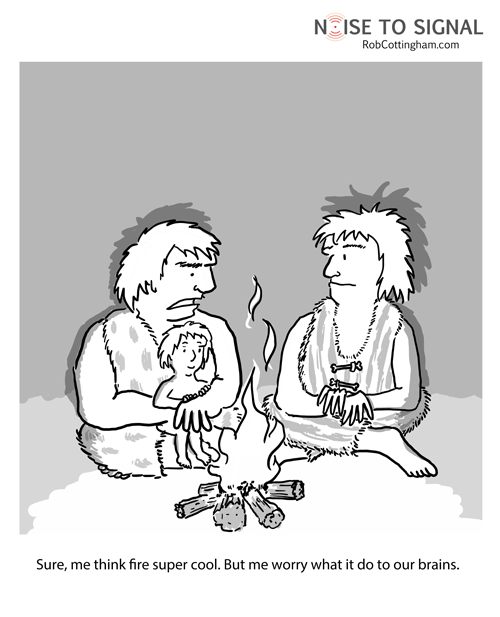

It isn’t easy to find the right balance between rah-rah bring-on-the-Bluetooth-brain-implants cheerleading and will nobody think of what it’s doing to the children?! fear-mongering. Certainly science doesn’t exactly offer definitive answers; Wikipedia conveniently gives you lots of evidence to support whichever position you feel like adopting.

(There’s also the argument that we’re pretty unlikely to turn away en masse from our screens, so let’s make the best of it.)

I circle around questions like these pretty often, but here’s where I keep finding myself landing:

At a time when we’re facing urgent civilization-level questions around energy, climate change, food security, massive income disparity and several other issues, we’ve also developed tools that can connect us in ways that were unfeasible one generation ago; fantastical two generations ago; and barely imaginable three generations ago.

We’d be crazy not to ask how they change us, but the idea that we should reject them out of hand because, well, have you seen the way kids congregate staring at their devices? strikes me as even crazier. We have to draw on those tools, and more importantly the connections they make possible, to answer those questions together.

Maybe Nicholas Carr’s right, and it’s turning us into shallow, short-term thinkers. (Attention, people who use tl;dr the way other people use commas: you’re not helping.) I find it easier to believe that maybe there’s some good in there, too, as Dr. Gary Small suggests, and there’s some hope of using the web to improve our thinking – while we apply a little attention to make sure we remain empathetic, decent people.